What is Cognitive Overload in Cybersecurity?

Cognitive overload isn’t a personal failing. It’s a design flaw. And in cybersecurity, it’s fast becoming one of the most exploitable weaknesses in...

(A.K.A: Why are people breaking quarantine & how it relates to your Digital Outliers.)

There is a shocking amount of non-adherence to clear and immediate directions regarding the coronavirus pandemic. Why is that?

Ah, the pesky humans are at it again.

People ‘doing the right thing’ (aka policy adherents) are expressing worry, disbelief, and outrage about those who are currently flouting the rules. How can they not be listening to directives from the government, health services, and experts from around the world? What are they doing having parties, going to church, shaking hands, and dancing together? What is wrong with them?

In Italy, mayors are literally *swearing* at their residents, shaming and insulting them, and even threatening to use flamethrowers on the people breaking quarantine and congregating.

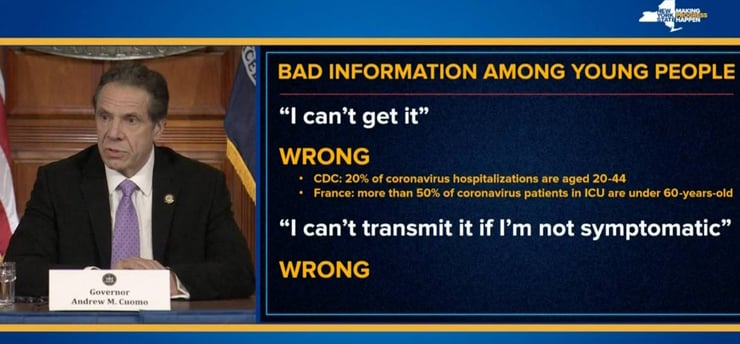

The governor of New York has chastised the many large groups of New Yorkers congregating in parks and going about “life as normal” when the city has a shelter-in-place order in effect.

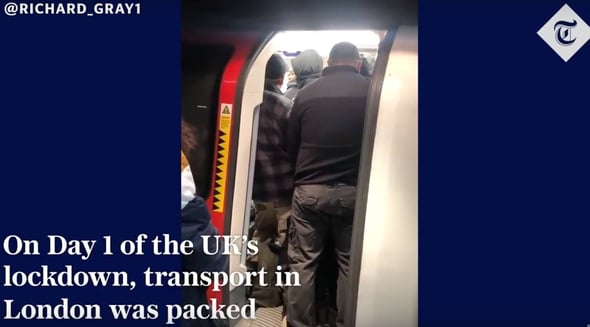

In London, the police have been called into parks to oust sunbathers and those treating stay-at-home mandates like a bank holiday. The UK government decided to bring down the hammer and go for a three-week near-total lockdown, citing the fact that a good portion of the population couldn’t stay away from the pub and was hoarding supplies and panic shopping as a reason for the draconian measures.

Ignorance isn’t it. With the level of media coverage and daily concern, I think we can rule out the possibility that these people haven’t heard about the spread or deadliness of COVID-19. Or that they didn’t know about the orders in place. A few might not know the most recent public safety orders from their city, region, or federal government. But lack of awareness can’t possibly explain the high number of people out and about.

To believe that rule-flouting stems from low intelligence is wrong as well. As much as we might call them idiots, the individuals and groups who are noncompliant can’t possibly all be either dumb or uneducated or both. For instance, we can assume US Senators are reasonably smart, and we know that many are highly educated, and yet they still crowd together in their chamber while debating stimulus legislation. Besides, saying people do something stupid because they are stupid prevents us from understanding the real problem.

When pressed as to why these rule-breakers give lots of reasons: the safety measures are overblown; their risk is low; they’re young and less susceptible; they’re old and set in their ways; they don’t know anyone with COVID-19; they don’t trust the government; they won’t care if they get sick or even die; they see themselves as rebels; they fancy themselves risk-takers. Maybe they feel like they don’t have to participate in this national or international social contract we are all agreeing to. Or they aren’t properly ‘engaged’ in how we want to work, as you know, a society (yes, that was sarcasm). There are plenty of reasons people will give for why they don’t listen to reason, advice, direct orders, and more. And these reasons come from different values, priorities, and sentiments. But these should be considered rational because it’s clearly not rational.

Ethan Decker, President of Applied Brand Science and marketing guru at The Cybermaniacs, says that a deeper understanding of why so many people are noncompliant comes from the Rogers innovation adoption curve that Everett Rogers developed back in the 1960s. Rogers ignored all the rationale people offered and instead focused on our herd tendencies. He noticed that new behaviors go through populations like a wave, and that adoption speed is shaped like a bell curve. A smaller group of innovators initiates the change, and then a larger group of early adopters follows. Once they normalize a behavior, the early majority and late majority follow along in their wake. Bringing up the rear are the laggards, a small group of holdouts who might never jump on the trend.

Critically, Decker notes, Rogers’ model got a significant adjustment in the 1990s from Geoffrey Moore: The Chasm. See, the early groups love novelty and embrace change. They prefer things that aren’t common. It’s not that they want to be different from others; they want to safely be part of the group that adopts things first. But the majority — the mainstream — are more resistant to change and like to wait until things are familiar and common to adopt them. You know the types from your own life.

This is exactly what we’re seeing play out globally with the response to the pandemic and people’s compliance with the orders. And seeing how often police have to ask people to go home in various countries, we’re starting to see a bit more of who these laggards are. Even in getting told off, facing fines, or causing public shame, they are perpetuating the risk. They are even putting the entire painful exercise we are all going through at risk. which is infuriating. I say this as I run a startup, look for funding, and homeschool three children under 10. I don’t mind the juggle, but I’m not doing this twice just because a tiny slice of the population would rather lark around the town square and spread the virus some more!)

To be effective with any public health program or any large-scale safety program, it’s imperative to understand what sits below the surface of the community you are trying to change. What is the culture, and what are the values, sentiments, and beliefs? These are the people factors that drive adherence or non-adherence around the change you’re trying to achieve.

In the case of the coronavirus isolation measures, we have the rather large stick of the government’s penalties and fines (and jail in Russia!). But we have lots of social pressure on various flavors. In some parts of the world, people comply to maintain group cohesion. In others they respect authority. Some places appeal to people’s self-interest and self-preservation.

During this crisis, I’ve seen great examples of influence techniques and tactics. Some groups are using visualization to help explain complex topics around pandemics, exponential growth, and epidemiology. (See the Flatten the Curve) Social media has provided thousands of examples of social proof: neighbors sharing highs and lows, celebrities pushing safety measures, and people sharing remote working set-ups (sometimes not as cyber safely as they should FYI). Humor and entertainment are being employed, with memes, gifs, and jokes getting everybody in on the action. Companies are showcasing what they are doing to help fight the virus, such as hotels offering free lodging for healthcare workers, or grocery stores having senior citizens’ hour first thing in the morning when stores are freshly stocked and cleaned.

Using positive messaging, good influence techniques, clear visualization, actionable language, and a bit of humor that centers on values-based behavior change CAN get a majority of that bell curve of people to do the right thing. Together, this has generated, for the most part, a high level of compliance. Around the globe, whole countries are adopting these behaviors and making them the new normal.

But then…. you have the last quadrant. The laggards.

So how do we reach that last 10% or 20% who don’t seem to be with the program? If carrots and cautions don’t work, do sticks? I don’t think so. How to bring the risky outliers into the fold is a question we’ve been trying to answer here at the Cybermaniacs, mostly as it relates to cyber security behaviors. We use a deeper and more comprehensive look at the human element within your organization. When we pull back and take a better look at the ‘who factor’ at organizations, we start by identifying and mapping digital tribes. They’re identified based on values, behavior, knowledge, sentiment, and perceptions. We tease out those brave and shiny early adopters, as well as identify the comfortable majority that will adhere to most governance and policy that’s rolled out. But then, the trickier bit. Who are the laggards? Where is the resistance to change? What are the deeper, implicit reasons behind this group’s highest-risk behaviors?

There is a great article in Psychology Today by Julia Shaw about this global phenomenon of non-compliance. What stood out to me was how we, the rule-followers, are feeling about these COVID-19 renegades:

“…just because someone is acting in a way that may lead to the death of others who become infected by COVID-19 does not mean they don’t care if their actions cause people to die. But our brains naturally jump to that conclusion. We assume that people who act badly, are bad, even in uncertain and complicated situations like a global pandemic.”

In other words, when people do things that have bad consequences, we assume it’s the person and not the situation, that’s at fault. We attribute the problem to them and their terrible character, not the circumstances. This common and universal bias is called the “fundamental attribution error.”

While the article is fantastic in explaining how we feel about them, and how we can use social proof and behavior contagion to perhaps coax the others into compliance, Shaw never really answers why the quarantine-breakers are doing what they are doing. If analyzed more closely, from a psychological or cultural standpoint, I wonder what the Gen Z partiers on spring break in Miami would say? What would the people picnicking at a park in London say? What would churchgoers group runners and team sportsters say? You don’t know until you ask the questions, do the surveys, get the assessments, and find out through objective means the drivers that feed the implicit culture and the reasons things are done.

Getting the laggards onboard requires the most creativity and insight. Novelty doesn’t work: they don’t want to be an early adopter. Familiarity doesn’t work: they’re not part of the mainstream. The answer is attainable, but you need to shed the fundamental attribution error and look to the specific context for each person or group, rather than looking for the answer within them.

When we flip the mirror onto ourselves and the businesses we work with, a company is made of people, processes, technology, assets, and value. Every company is going to have a different map of digital tribes. Every company is going to have different regulatory pressure or policy requirements, depending on a range of factors such as size, countries of operation, industry, safety requirements, and more.

You don’t know who you are as a company until you do the work to get the data and try to understand where the human risk factors are. (And for my UBEA fans, I don’t think that something that profound can be found only by looking at keystrokes or network behavior. You have to get messy and, you know, talk to your humans.) The underpinning cultural elements can help you find a way to communicate the change and properly inspire the laggards. I think are not only the greatest win but could be your greatest advocates, if only you can get on their level and give them the reasons and tools to change. Isn’t it sometimes the case that the greatest advocates for change are the people who have gone through the greatest transformations themselves? Whether that be recovered alcoholics who are now sponsors, ex-smokers who convince others to quit, the fantastic people who have achieved huge weight loss and fitness goals, or people who have recovered from diseases and run the charity marathon every year. What if you could find the riskiest people at your company and turn them into champions for cyber security?

While we ponder the best way to do all these things, we hope you all stay home, stay safe, and keep the faith alive.

We close with a reinvested classic from Neil Diamond. Talk about using humor and fun to reinforce a message!!

Cognitive overload isn’t a personal failing. It’s a design flaw. And in cybersecurity, it’s fast becoming one of the most exploitable weaknesses in...

5 min read

Insight from our founder of Cybermaniacs - here’s what I’d say to a boardroom full of CISOs and execs reading the State of the Ransomware Report: ...

5 min read

Does cybersecurity have anything to do with corporate wellness? Absolutely. Stress and burnout aren’t just personal challenges—they’re security...

3 min read

Subscribe to our newsletters for the latest news and insights.

Stay updated with best practices to enhance your workforce.

Get the latest on strategic risk for Executives and Managers.